Research

Microbes are a critical component of the diversity and function of terrestrial and marine ecosystems. They receive a large direct share of net primary productivity and play a crucial role in global carbon and nitrogen cycles. In the vast majority of environments however, the identity and function of these organisms remains unknown. Even less understood are the key factors that determine the distribution and abundance of microbial species, and how their presence, in turn, affects their environment and/or hosts. My lab works at the intersection of biogeography, phylogenetics and community ecology theory to identify patterns and processes that underpin the assembly and function of microbial biodiversity.

Anthony is the Principal Investigator of the Integrative Center for Environmental Microbiomes and Human Health. This NIH-funded Center of Biomedical Excellence provides funding, infrastructure, training and mentorship for new investigators in this vanguard, transdisciplinary field. Learn more about the ICEMHH here.

Microbial Roles In Foodwebs

Microbiomes determine rates of energy transferred along food chains, a parameter which directly governs the number of trophic levels, and the diversity of species withing them. To assess linkages between microbiomes and food chain efficiency, we have developed a tractable experimental system leveraging the simple system of tank bromeliads and their resident invertebrates. By manipulating hosts, microbes and their environments, we are gaining mechanistic insights into ecosystem/microbiome interactions.

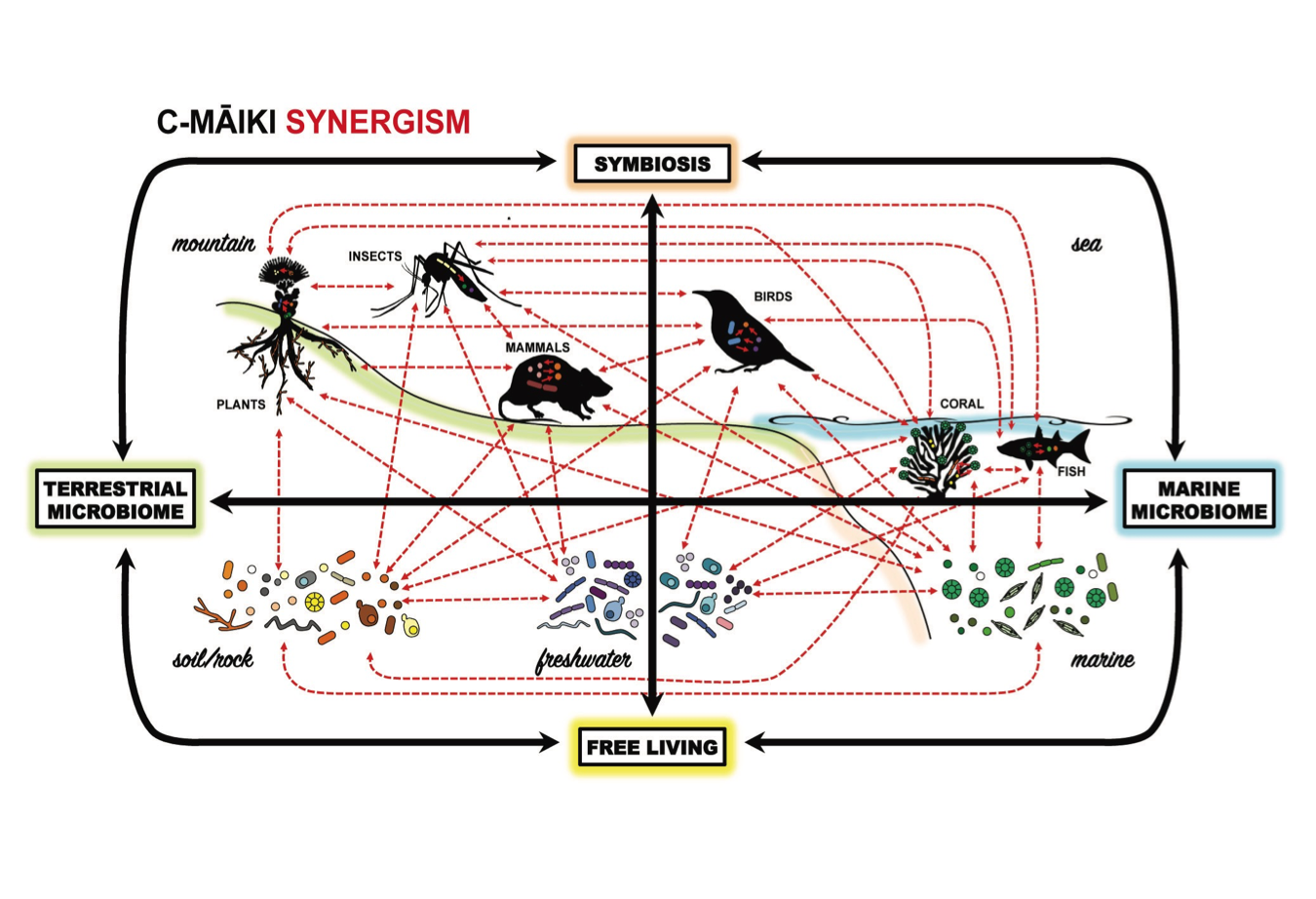

Habit Connectivity and Microbial Resevoirs

Acquiring the “right” microbiome at the “right” time is essential, since an organism’s accessory microbiome plays nearly as large a role in determining an organism’s health and fitness as does that organism’s genes. However, the process governing microbiome formation is more complexed and less understood. Where, then, is the source of these beneficial microbes that are so critical for human and ecosystem services? How does the environment shape microbiomes? How does the environment shape host and ecosystem function via microbiomes?

To address these questions, we have established the first ecosystem microbiome observatory in the Waimea valley on Oʻahu’s North Shore. In fewer than 8 km, the main rivers of Waimea valley plunge from a high elevation rain forest, over cascading waterfalls, into a protected estuary and out over one of the most pristine coral reefs on Oʻahu. This short span represents a steep elevation and precipitation gradient, ranging from over 5 m of rainfall at the river’s headwaters to around 1 m at the coast. This offers a wide diversity of terrestrial, riverine and marine habitats in close proximity to each other. Within a series of plots in each of these habitats, we have surveyed around 2,000 organisms and substrates to gain a sense of microbial source and sink dynamics at a landscape level.

Diversity and Distribution of Marine Fungi

Fungi are critical, though largely overlooked, member of marine microbial communities. Through various lab projects and collaborations, we are exploring the diversity and distributions of marine fungi on a global scale, as well as their roles in host health and ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling. Phytoplankton, corals, algae, seagrasses and sediments are some of our focal habitats so far. We are particularly interested in the marine Malassezia, which are surprisingly widespread.

Applied Conservation Using Fungal Diversity

Our lab is always eager to harness the power of fungi to address pressing needs in Hawaiian and global conservation. We have studied how fungi can feed endangered snails, restore endangered plants, and break down plastic waste. With somewhere around one billion years of evolutionary history under their belts, we suspect that fungi have even greater tricks under their sleeves.